WAVE and the Einstein Telescope

What does WAVE have to do with gravitational wave detection? Why are seismic sensor networks so important, especially for the next generation of gravitational wave detectors like the Einstein Telescope (ET)? And what exactly are gravitational waves, and why are scientists so eager to detect them?

Let’s delve deeper into the world of gravitational wave detection and its connection to the WAVE project!

Gravitational Waves

When massive celestial bodies like black holes merge, they spiral around each other, drawing closer and spinning faster. This motion releases gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime itself. These waves stretch and compress spacetime, though by incredibly tiny amounts. For instance, if a gravitational wave passed between Earth and the Sun, the 150-million-kilometer distance would change by less than an angstrom, smaller than an atom!

Despite these tiny distortions, gravitational waves reveal details about the universe’s most energetic events. The first detection, GW150914, in 2015 by Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory LIGO, captured a black hole merger 1.4 billion light-years away, confirming Einstein’s theory and marking a new era in astronomy. Gravitational waves also come from neutron star collisions, like the 2017 GW170817 event, where scientists observed both gravitational waves and light, launching multi-messenger astronomy. Nearly 400 gravitational wave events have been detected so far.

Unlike electromagnetic telescopes that see the universe, gravitational wave detectors let us hear it. But detecting these waves is challenging because they are really really tiny, requiring incredibly sensitive instruments.

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

Gravitational wave detectors, like LIGO, measure tiny distance changes between two suspended mirrors (which we call test masses), 4 km apart, using a laser interferometer. These mirrors are suspended on ultra-thin strings to simulate free-fall and isolate them from ground vibrations, reducing seismic noise interference. The mirrors, acting as test masses for gravitational waves, perfectly reflect laser light, allowing precise measurement of light travel time in two perpendicular directions. When a gravitational wave passes, it stretches one interferometer arm while compressing the other, causing a shift in optical power that’s detected by a photodiode, revealing the gravitational wave signal.

We need to detect very small position changes down to 1e-18 meters, so the test masses must stay almost perfectly still. However, many noise sources, from ground vibrations to local gravitational fluctuations (“Newtonian noise”), can disturb the masses. Even nearby footsteps can create slight gravitational pulls! Reducing this Newtonian noise is key to enhancing gravitational wave detection.

Seismic noise

Seismic waves can result from tectonic shifts, human activity, ocean waves, and many other sources. They can produce noise in the gravitational wave detector by shaking it and moving the test masses. You can learn more about seismic waves here.

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

To suppress seismic noise, we make the suspensions of the mirrors super long, and combine several stages, so we actually have a multistage-pendulum, on which shiny mirrors are hanging. This is what we call passive isolation system. But this is not enough, and, additionally, the suspensions produce resonance frequencies (you know these frequencies when bridges can be destroyed), which needs to be damped, actively. Active noise cancellation involves measuring the noise from the ground or the system, and then either adjusting components in the detector (such as the suspensions) to counteract this noise during operation, or to remove the noise during the data analysis. For this we use, again, laser interferometers! Yes, we have small laser interferometer to improve the big laser interferometer gravitational wave detector.. But we also use seismic instruments like geophones and seismometers.

And this is where WAVE comes in!

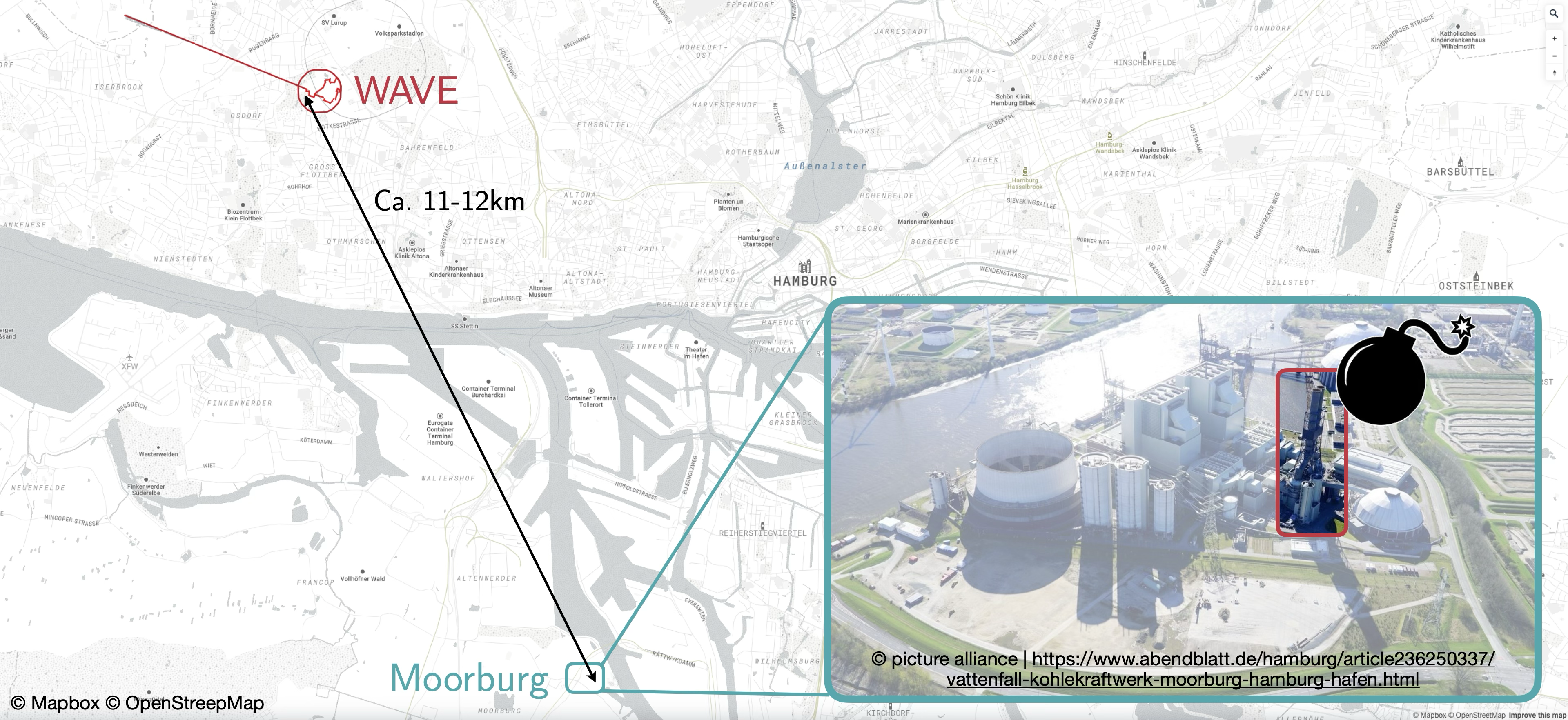

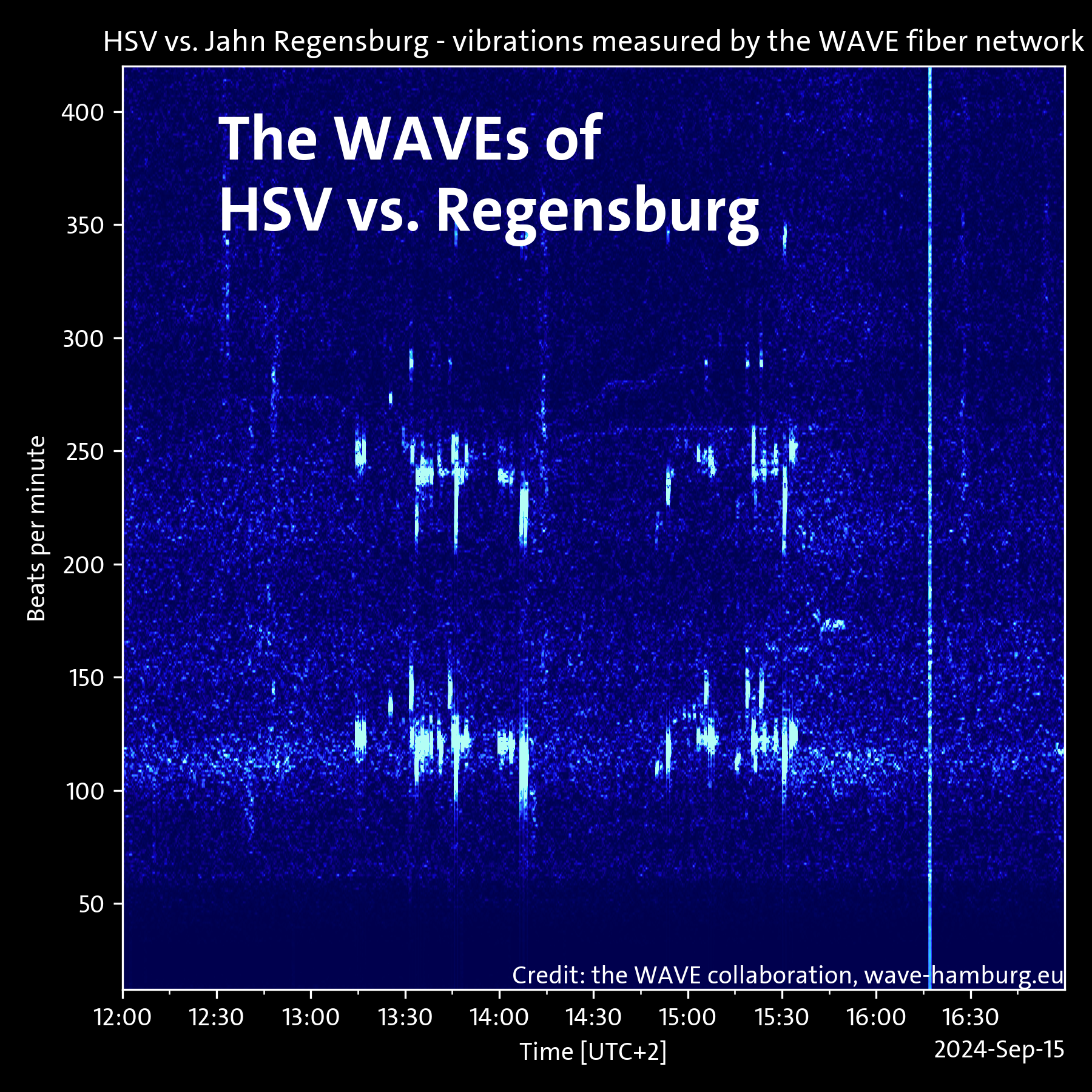

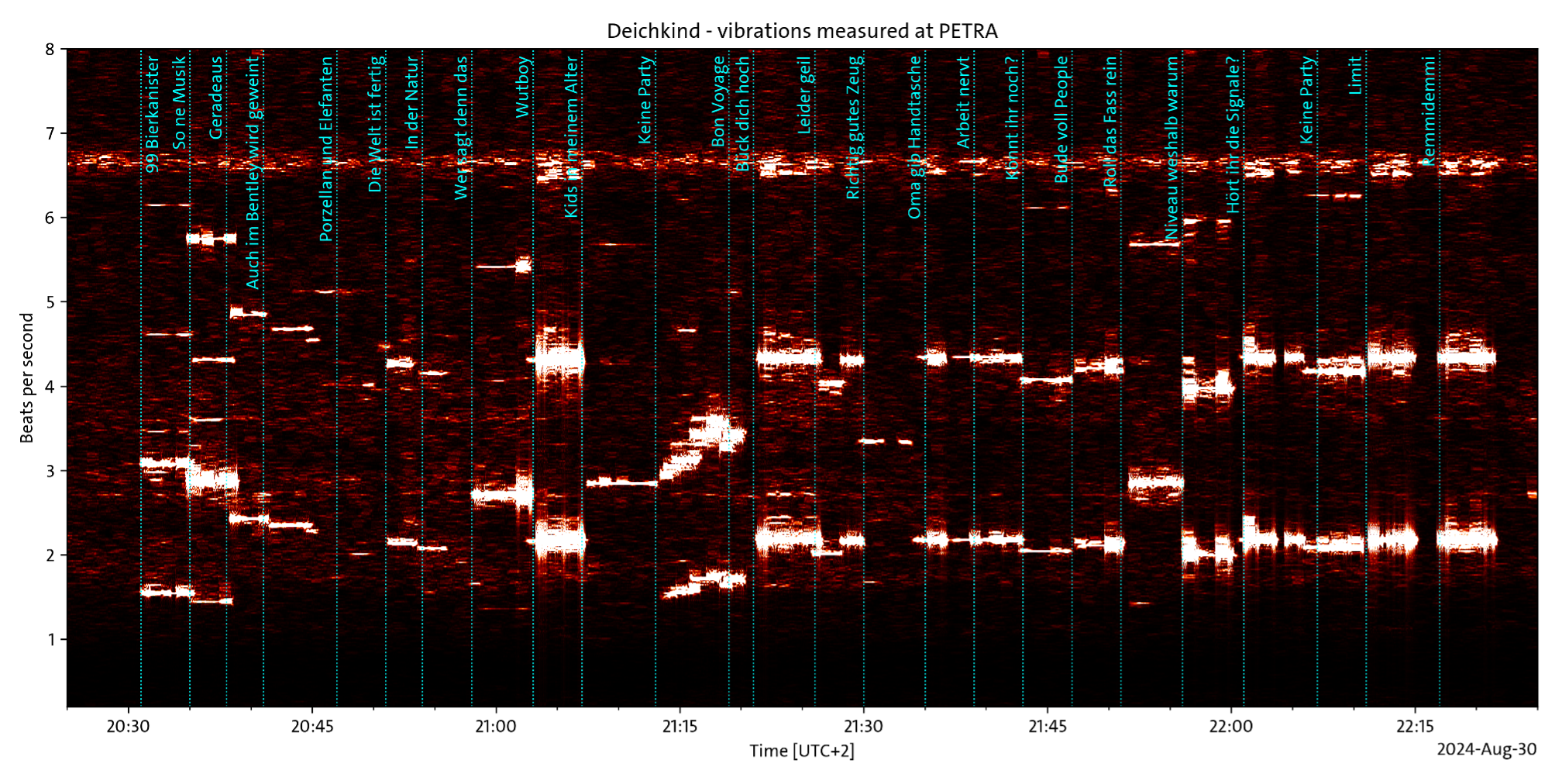

Could Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) help? Is a large seismic sensor network like WAVE beneficial for gravitational wave detectors? And can we even address the challenging issue of non-shieldable Newtonian noise, a problem yet to be solved in the future Einstein Telescope? These are the exciting questions that WAVE scientists are exploring!

Newtonian noise

As we aim to improve the sensitivity of gravitational wave detectors, such as the Einstein Telescope (ET), Newtonian noise, caused, for example, by seismic noise, will limit the sensitivity and thus the detection of cool cosmological events which are even heavier or further away than those detected so far. Seismic waves cause tiny fluctuations in ground density, effectively mass changes, which in turn alter the local gravitational force. These fluctuations near a sensitive detector can interfere with its ability to detect gravitational waves, making Newtonian noise a significant challenge.

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

Suspensions can’t block Newtonian noise because it’s a gravitational force, and gravity can’t be shielded. To suppress it, we need new strategies. One idea is to measure Newtonian noise and subtract it from the gravitational wave signal. But Newtonian noise is incredibly faint, making it difficult to detect. While some scientists are developing Newtonian noise sensors, these are as complex to build as gravitational wave detectors. In fact, a gravitational wave detector is itself a Newtonian noise sensor!

Instead of measuring Newtonian noise directly, we can track its source — seismic waves!

That’s one reason for building the WAVE network!

The goal is to capture the full seismic wave field—often quite complex—and use this data to predict Newtonian noise through a smart algorithm or machine learning. Since the density of the ground affects how seismic waves create Newtonian noise, precise, site-specific measurements are crucial. This approach needs extensive data to accurately capture the complex seismic wave field and predict Newtonian noise, especially for sensitive detectors like the Einstein Telescope. To gather this data, Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) can be used, providing thousands of sensors to create a detailed seismic picture.

WAVE

Since DAS uses optical fibers, it functions like an array of thousands of seismic sensors spaced every meter along kilometers of fiber. By wrapping the fiber around the vacuum chambers and beam path of the detector, it can precisely map environmental vibration, creating detailed profiles that show noise levels throughout the detector. This detailed mapping enables noise hunting, allowing us to improve noise cancellation not only for seismic and Newtonian noise but maybe even for unexpected noise sources we may not yet fully understand. DAS could reveal unknown noise origins, offering new insights and enhancing the overall sensitivity of the detector.

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

While DAS has not been implemented in a gravitational wave detector to date, there are plans to implement it especially in future generation detectors such as the Einstein Telescope, which is a planned detector in Europe.

Some additional information

Einstein Telescope (ET)

The Einstein Telescope ET will be Europe’s next-generation gravitational wave detector, designed to improve sensitivity by 1 order of magnitude compared to current detectors like LIGO and reach lower frequencies (1-10 Hz), where seismic and Newtonian noise must be suppressed by even one million! Its development will involve a major multinational effort over the next decade, with members of the WAVE team contributing strategies and sensors for seismic and Newtonian noise cancellation.

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

Credit: K.-S. Isleif

ET will be larger, with 10 km long interferometer arms, increasing sensitivity to detect smaller gravitational waves. It will also feature three overlapping interferometers arranged in an isosceles triangle, with each side containing two arms, thus multiple detectors in one experiment.

Additionally, the Einstein Telescope ET will be built 200-300 meters underground to reduce seismic and ambient noise, crucial for low-frequency detection. However, large seismic sensor arrays, like those achieved through Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) by simply deploying fibers, are being investigated by WAVE. We are exploring how to optimally use this wealth of data to map and cancel both seismic and Newtonian noise in the ET.

More Gravitational Wave Detectors - current and planned

There are multiple gravitational wave detectors which are already in operation, while even more are being planned. The detectors currently in operation are the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory LIGO in the USA, KAGRA in Japan and VIRGO in Italy. For a future generation of detectors, there are plans to build the Einstein Telescope ET in Europe and Cosmic Explorer CE in the USA. While they all rely on the Michelson interferometer topology, the detectors vary both in size and sensitivity. LIGO has armlengths of about 4 km, while Virgo has 3 km.

In addition to the earthbound detectors, there will be a gravitational wave detector which will operate in space, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna LISA. This detector will have three satellites and have a different interferometry scheme and will have arm lengths of 2.5 Million kilometers! The satelites will trail behind earth while sending laser beams inbetween them in a giant triangle. This will enable the detection of low frequency gravitational waves. These waves come from older parts of the universe. The planned launch date for the LISA mission is in 2035.